OECD FORUM 2018 – RESKILLING: HOW DIFFICULT IS IT?

“Become who you are. Reskill and find your next job!” Such is the promise of a reskilling company.

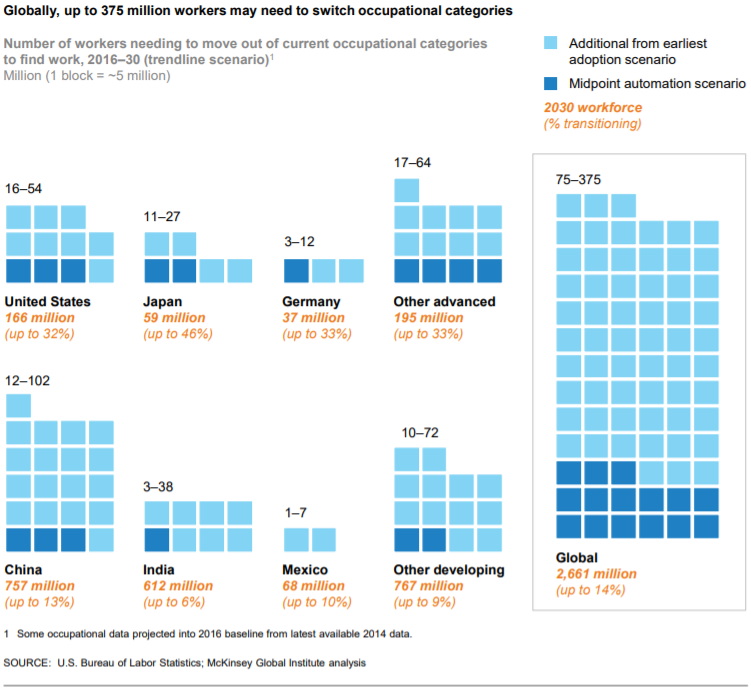

With increasing automation, “60 million to 375 million individuals around the world may need to transition to new occupational categories by 2030. Nearly all jobs will involve a shifting mix of tasks and activities”, according to a 2017 McKinsey report Jobs lost, jobs gained: Workforce transitions in a time of automation.

LIFELONG LEARNING

Effective systems for lifelong learning and workplace training will be essential. Upgrading skills should match the pace of technological change and retraining should be accessed when needed. As much as 82% of executives at companies with more than USD 100 million in annual revenues believe retraining and reskilling to be at least half of the answer to addressing their skills gap, according to another McKinsey survey.

The skills mismatch is obvious. “We see all this youth unemployment and now adult unemployment and yet 40% of the employers are saying they can’t find the talent they need”, pointed out Shea Gopaul, the Executive Director of the Global Apprenticeship Network (GAN).

What came as a surprise to her was that although you would expect companies to need IT or STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) skills, what they were calling for was ‘soft skills’ – collaboration and communication skills, working in teams, critical thinking, creativity and adaptability.

The human factor plays an essential role in the reskilling process. The Z-generation, Ms. Gopaul warned, has had enough of computers. “Even with e-apprenticeships, 40% is online but 60% has to be with human contact”.

- Learning and Earning at Full Force: A call to leaders from Malala Fund

- matchED: Matching Education and Digitalization

Reskilling is not a straight equation; Jean-Michel Blanquer, the French Minister for Education reminded us it is not just about supply meeting demand. It is essentially a human process: people digging down deep within themselves to bring new skills to the surface, skills that can be linked to a job but also to a “savoir-être” involving social and emotional skills.

Hence the importance of encouraging those who need to learn new skills. Mr. Blanquer stressed how rewarding synergies can be developed when those who reskill through vocational education mentor apprentices. What is also interesting about the apprenticeship model is the potential for intergenerational conversation: the young person can help the adult, whom they in turn can learn from, indicated Ms. Gopaul.

Yet, reskilling may not always work. In Janesville: An American Story, its author Amy Goldstein found that, after layoffs began in Janesville, Wisconsin, in 2008, “people who had not gone back to school were by mid-2011 more likely to have a job than those who had retrained” and when they did find a job, their pay drop was higher.

What do these sobering findings tell us? First, reskilling is not just about skills and attitude, it is also about identity. Finding the strength to reinvent yourself and do your homework next to your children is not easy. And second, the local context matters. There were simply not many jobs waiting for the automotive workers who had reskilled, Ms. Goldstein recalls. The few jobs that had been available had probably been seized by those who had not spent time retraining. This also raises questions of mobility and the wider context.

Who is responsible for making reskilling happen and work?

- Find out more about the OECD’s work on Skills

- Learn more about the OECD’s work on Education

Hassan Yussuff, President of the Canadian Labour Congress, stressed that it is the government’s role to bring unions, employers and educators together. Ms. Gopaul also pointed out that reskilling is everybody’s responsibility: it is the responsibility of the individualas well.

We all have a role to play, agreed Mr. Blanquer. We need to be effective actors and promoters of change. The economy is not something that just falls on us like meteorites. We should shape and guide it.

Because in the end, this is also about the society we want. We should not lose sight of the bigger picture, warned Andreas Schleicher, Director of the OECD’s Education and Skills department and Special Advisor on Education Policy to the Secretary-General. “Employers have one important voice, but it shouldn’t be the only voice. Society needs to think harder about the long term”.

Issues such as gender and climate change need to be addressed, Mr. Yussuff pointed out. How do we stop focusing on male-dominated industries and help women to reskill? How do we get workers with the skills that will help us rise to the climate change challenge?

Mr. Schleicher’s wake-up call rang loud and clear: “We’ve grown comfortable with so many things. In schools, we teach people our truth of today rather than helping them to question the established wisdom of our times, to think forward, anticipate, be open to the novelty. We have a consumer attitude to education. We need to become actors. Working and learning need to become really integrated”.

Lifelong learning starts early. If you do not lay the right foundations, it becomes an uphill struggle, he warned. Mr. Blanquer also highlighted that education systems should be forward-looking and prepare younger generations for jobs that will exist.

The world has changed and the labour market will undergo further tectonic shifts. Yet, only one in five people identify changing labour markets as a megatrend that could impact their retirement, according to the 2018 Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey.Catherine Collinson, President of the Transamerica Institute and Executive Director of the Aegon Center for Longevity & Retirement warned us, “Any disruption in our working life can have even greater consequences when we retire. We need to raise awareness of the issue”. Financial skills are also essential to plan for our future, she pointed out. Yet, only three in ten people answered three very basic financial questions correctly. Mr. Yussuff also stressed that a lack of basic numeracy and literacy skills makes older workers particularly vulnerable in the job market.

Ms. Gopaul identified a best practice example: AT&T’s programme to reskill people who are losing their jobs in which “you do a part-time apprenticeship in your last year in a new area and a new field”.

We used to learn to do the work but now learning has become the work, concluded Mr. Schleicher. “The learning part may still be the easy part of lifelong learning. Our capacity to unlearn and to relearn when the context changes, that’s maybe the real challenge”.

As upgrade our skills to match the pace of technological change, let’s not forget what it means to be human. Mr. Schleicher concluded that “Education has won the race with technology throughout history, but I am not so sure that it is going to last. We should not try to substitute artificial intelligence, but rather complement it. Artificial intelligence forces us to think much harder about what it means to be human”.

Read the new OECD report Seven Questions about Apprenticeships: Answers from International Experience released 15 October 2018 at 15:00 Paris time

Watch the Reskilling: How difficult is it? webcast again and see photos from the session