CAREER READINESS IN THE PANDEMIC

How can we tell if young people are likely to be benefit from the career guidance and development that they engage in? Now, more than ever as the Covid healthcare emergency morphs into an employment crisis, it is important to reflect on what works and why? The only sure fire way to know is to track students over time into their adult lives and see what in their childhood and youth has made a difference. We can do this through analysis of national longitudinal databases. Following thousands of individuals from childhood to adulthood, we can find associations between attitudes and experiences and better outcomes in adulthood. The longitudinal data tells us how well you can expect a typical girl or boy to do in work given their academic abilities, qualifications, social characteristics and how strong the economy they enter is. We can then look to see if participation in any career-related activity ultimately made a difference.

This year at the OECD we have been reviewing the academic literature to identify examples of teenage career-related indicators of adult employment outcomes.

https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/career-ready_e1503534-en

We find that across three coherent areas, there is compelling evidence across different international studies. In a new working paper, we set out these findings as they relate to how teenagers think about, explore and experience the future:

Thinking about the future

- career certainty: ability to name a job expected at age 30

- career ambition: interest in progressing to higher education and professional/managerial employment

- career alignment: matching of occupational and educational expectations

Exploring the future

- career conversations: speaking to an adult about a career of interest

- occupational preparation: participation in short occupationally-specific courses within general programmes of education

- school-mediated work exploration: participation in job fairs, job shadowing and workplace visits.

Experiencing to the future

- part-time employment: participation in paid part-time or seasonal work

- internships: participation in school-mediated work placements

- volunteering: participation in community-based volunteering

In the working paper, we then draw on data from the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) which surveys hundreds of thousands of 15 year-olds around the world to compare participation levels between and within countries. The paper provides a foundation for futher work over the next twelve months. We will undertake new work with databases from more countries to understand how these teenage attributes can make a difference to adult lives. By the end of 2021, we plan to have created new tools for policy and practice making use of the indicators.

What a difference a (career) conversation makes

For people who don’t work in career guidance perhaps the most surprising indicator would be career conversations. Can it really make such a difference to simply speak to someone, anyone about a job of interest? Reviewing the academic literature, we find that many longitudinal studies ask teenagers if they have spoken to someone, often subject teachers, about their career plans. Findings from six US, UK and Australian studies are summarised in the paper. Analysis by Elnaz Kashefpakdel when at Education and Employers, for example, found that young adults were up to 24% less likely to be NEET than peers if they’d spoken to a teacher about their career plans while in school.

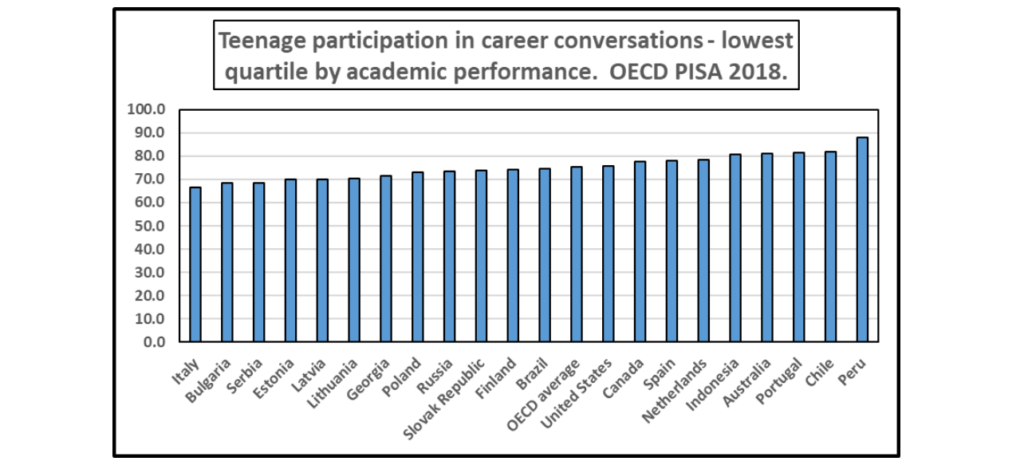

PISA 2018 data shows that the proportion of young people who reported having a career conversation with an adult to vary considerably by country and social background. Worryingly, it is low achievers likely to leave school at early opportunity who are among those least likely to report speaking to an adult.

When a young person reports that they took part in a career conversation, two things might be happening. It is possible that they gained something useful for their school to work transitions. Their might have career ambitions and envisaged pathways might have been challenged or clarified. They may come away from the encounter encouraged or more determined. They might only realise months or years later the value of the conversation they face new circumstances. Of course, the conversation itself may never prove to be of value, though we can surmise that the more conversations they take part in, the more likely it will be that they gain new and useful information.

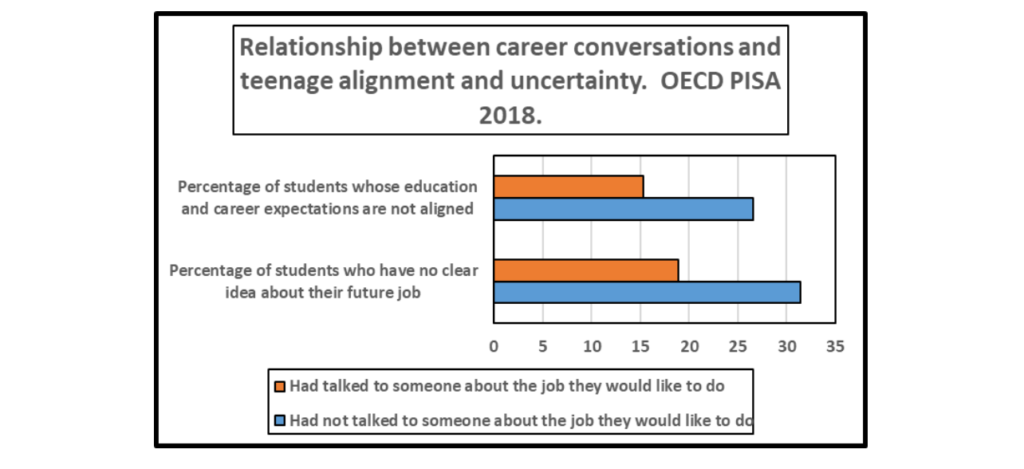

A second perspective provides perhaps greater confidence as to why a teenage career conversation might be associated with better adult employment outcomes. We can assume that the young conversationalist is exploring potential roles in the jobs market: that they are actively seeking out new information or sources of support. Taking part in a career conversation provides some evidence that a student is demonstrating a sense of agency in their transition and/or that they are being supported by members of their social network. In either case, confidence rises that they are thinking critically about the relationship between their education and ultimate employment. In the PISA 2018 data we use statistical analysis to look at the relationship between having taken part in a career conversation and two other positive indicators of adult employment outcomes: career certainty and alignment. We find that 15 year-olds who agree that they had “talked to someone about the job they would like to do when they finish their education” were much more likely to have a clear career ambition (career certainty) and to understand the education needed to achieve their occupational goal (career alignment).

Even with statistical controls in place for a range of personal and social characteristics including performance of the PISA tests in reading, mathematics and science, the relationship holds. For practitioners, therefore, a simple question – have you talked to anyone about the job you would like to do when you finish education? – provides valuable insight. The answer gives a sense of the agency that the student is demonstrating and, in combination with other indicators, builds a picture of how they well are approaching their transitions.

Next steps: get involved

Over the next twelve months, the OECD will be undertaking new analysis of national longitudinal databases, publishing guidance papers based on the findings and sharing examples of effective practice around the world. You can sign up to an informal stakeholder group to stay in touch with the work and share practice that you are involved in. To do so, email me at [email protected]